This article has been written by Adele Greedy-Vogel

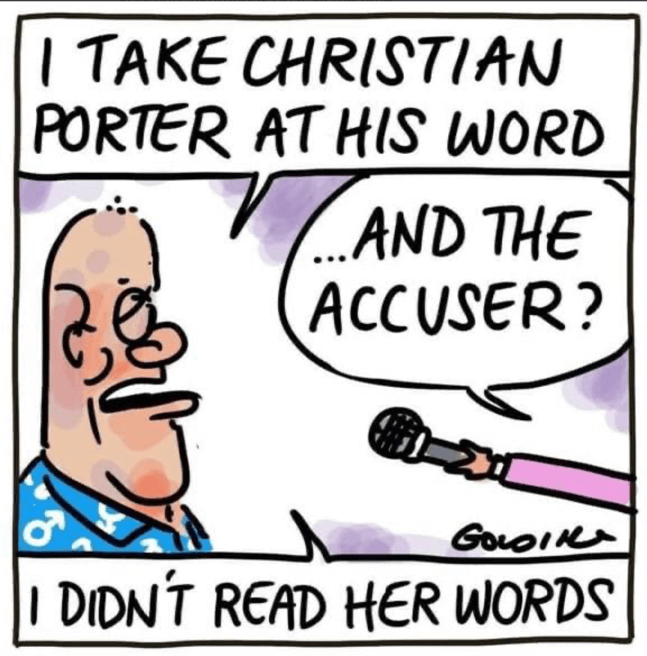

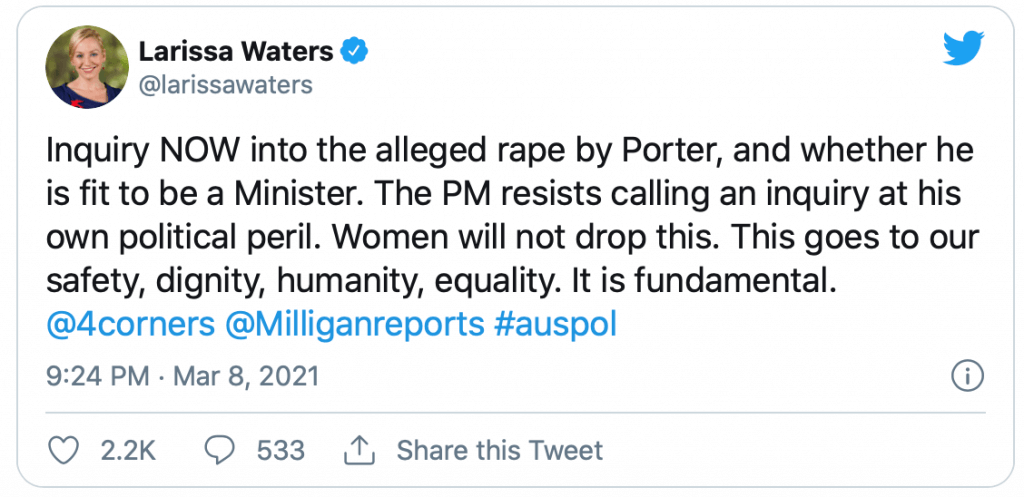

In just the past two months, we have seen the rise of Grace Tame as Australian of the Year speaking out again child sexual violence with the #LetHerSpeak campaign. We’ve also witnessed the rejection of Christian Porter’s historical rape allegation and the attempted silencing of Brittany Higgins.

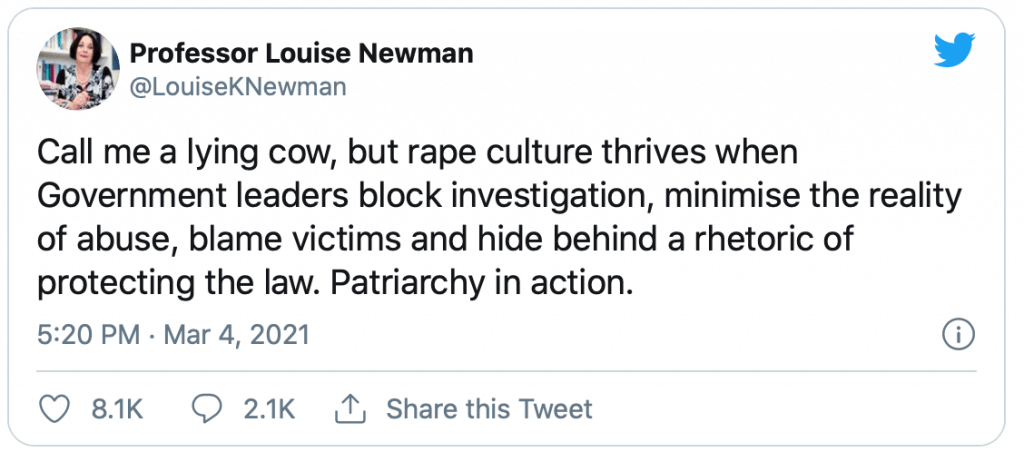

As women, many of us are experiencing a deep melancholia. An identification with the women we see represented in Australian news and being reminded of how we are constantly silenced by those who do not want to acknowledge our pain. I am (rightfully) angry and I will not be silenced.

The statistics could be considered horrific – 1 in 5 Australian women have experienced sexual violence since the age of 15. One of the most shocking things about sexual violence is how little our government doing to respond to it. The government is well educated about the facts. However, from the public’s perspective, it does little to change their emotional connection to sexual violence.

We should be asking, #WhySoManyMen? We should also be asking why do so many Australians, including Scott Morrison, reject sexual violence as a possibility?

Julia Kristeva and abjection

I want to introduce a concept that I think needs to be introduced to our collective vocabulary: the abject. The abject is a complex concept developed by philosopher, psychoanalyst and feminist Julia Kristeva in her 1980 book The Powers of Horror.

Abjection is a social and psychological process by which things such as waste, menstruation, corpses and rotting food are cast aside. They are cast aside because they create powerful emotional responses like horror and disgust. The process of abjection happens when we are faced with something that breaks down the distinction between self and other.

Abjection does not confirm, it breaks down, destroys, destructs, it is “the place where all meaning collapses” and the stable self along with it.

– Julia Kristeva in The Powers of Horror

Imagine you blow your nose to find thick, gooey, green snot on your tissue. Now lick it. If you’re like most people, the idea of doing so will gross you out.

You have snot in your nose all the time and probably frequently swallow it (ew!). However, by blowing your nose you make the snot something apart from you. And it’s not like any other object outside of you, because it came from you. After you blew your nose, your snot became a special kind of other: a gross, icky, grotty other. An other that has been abjected.

Sexual violence is repulsive

Think of our government, our community and even our families as social bodies. By speaking out against these social bodies, survivors of sexual violence become something outside of them. But because the violence was perpetrated within these social bodies, survivors become also something from them. They are survivors because of and in spite of the violence that they experienced. Survivors and their voices are abjected because sexual violence is infuriatingly repulsive, and the institutions and people who perpetuate the violence refuse to acknowledge it as part of their story.

Sexual violence is currently pervading and disturbing Australian institutions – our government, our schools, our churches. We know this because of initiatives such as the National Redress Scheme and Chantel Contos’ petition. Yet sexual violence is still subconsciously rejected as a possibility. Why?

Institutions do this to protect themselves from the horror of the act, but in doing so, render themselves unable to formulate appropriate responses. They silence, they invalidate and they abject.

The Guardian writes, “Two-thirds of Australians think government more interested in protecting itself than women”.

Solidarity among women

Women all over Australia are outraged. Women are speaking up and speaking out. Through our stories we are destabilising the power that tries to define us. We are calling for not only answers, but action. In Revolt, She Said Julia Kristeva wrote, “I revolt, therefore we are still to come.” The revolution of solidarity amongst women in Australia has only just begun.

“One voice, your voice, and our collective voices can make a difference. We are on the precipice of a revolution whose call to action needs to be heard loud and clear”

– Grace Tame, National Press Club

Adele Greedy-Vogel is a Philosophy and Economics student at The University of Queensland. She is extremely passionate about feminist philosophy, semiotics and social justice. She identifies as a Coda (Child of Deaf Adults) and a really, really short person. In 2021, Adele was awarded the prestigious New Colombo Plan scholarship and plans to live, work and study in Thailand. All views are her own. Connect with Adele on LinkedIn.